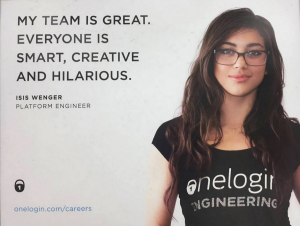

In the weeks after Isis Wenger’s #ILookLikeAnEngineer movement, I’ve been thinking a lot about labels and preconceived notions—of engineers, developers, gamers. This isn’t a new problem: if I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard “You don’t look like a gamer/game developer,” I could probably fund my own studio. Needless to say #ILookLikeAnEngineer struck a chord, and I think it’s important to draw attention to what we think certain groups “look like.” Games has been having this conversation for years, but I still have a lot to internalize.

In the weeks after Isis Wenger’s #ILookLikeAnEngineer movement, I’ve been thinking a lot about labels and preconceived notions—of engineers, developers, gamers. This isn’t a new problem: if I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard “You don’t look like a gamer/game developer,” I could probably fund my own studio. Needless to say #ILookLikeAnEngineer struck a chord, and I think it’s important to draw attention to what we think certain groups “look like.” Games has been having this conversation for years, but I still have a lot to internalize.

Labels are interesting things. Despite working on a Computer Science PhD, teaching programming, and getting a job in which program all day, I haven’t really ever identified as an engineer. I don’t code for the beauty of coding. While I try to write efficient, maintainable code, I also know that sometimes quick and dirty code needs to happen, and that sort of thing doesn’t bother me the way it does some people. If I stopped coding tomorrow, I would miss it, but it wouldn’t tear away pieces of my happiness the way an absence from writing does.

In other words, I don’t live up to my own stereotypes of what an engineer is.

And when you put it that way, it’s glaringly obvious that I’ve been looking at it the wrong way.

A few weeks ago I had a conversation with some engineers on my team. They’re all extremely talented, awesome people, and they’ve been nothing but nice and supportive since I joined.

One afternoon over froyo, we started talking about what it means to be an engineer. I confessed that I really feel more like a designer; I really don’t think of myself as “an engineer.”

“Really?” one of them asked. “But you code all day! You’re definitely an engineer.”

I appreciated the sentiment. Living in an interdisciplinary field, I’m usually the one who’s good at “that other thing.” Writers and eLit folks call me a “games person.” Game engineers call me a “designer” or if I’m lucky a “narrative designer.” Designers call me an “engineer.”

Very rarely have I had people outside of my awesome Santa Cruz narradev community say “hi, you’re one of us!” Yet here were the engineers, welcoming me wholeheartedly. After all, we’d bonded over games and various nerdities, was I saying I didn’t want to be an engineer? I got nervous. I didn’t want them to take it that way.

I explained that I really wasn’t as good a programmer as them. I explained the thing about the seeing the beauty in code. I intimated—but didn’t actually say—that I see them all in a whole other league in terms of technical skill. I’m not one of these people who’s been coding since I was 12.

The conversation shifted into how we use labels, and an interesting point emerged. Some labels are ones we give to ourselves; they’re how we identify. Others are labels given to us based on what we do. If you kill someone, the engineers argued, you don’t get to decide whether you’re a murderer.

But there’s an interesting process of internalization of labels that I saw happening in myself. I resisted calling myself an engineer, even though it was validating for others to see me as one, because I didn’t want to be put in a box.

I want to be an engineer. But not if it means giving up writing. Or design.

I was looking at it the wrong way.

Labels should be lenses, not boxes.

The real question is not “what does this label mean I can or can’t be?” but instead “what can I learn by looking at myself in this context?”

We talk a lot about intersectionality in identity politics, but many explanations or depictions of intersectionality still imply boxes. I am white, female, cisgendered, able-bodied, and so on. Ticking off these various checkmarks feels as if I’m tearing myself into pieces that fit into many different boxes, none of them wholly me. Intersectionality is supposed to solve this problem by taking multiple privilege scales into account, but certain models still quantitatively measure based on the sum of privileges across different categories—some are worth more, some less.

We talk a lot about intersectionality in identity politics, but many explanations or depictions of intersectionality still imply boxes. I am white, female, cisgendered, able-bodied, and so on. Ticking off these various checkmarks feels as if I’m tearing myself into pieces that fit into many different boxes, none of them wholly me. Intersectionality is supposed to solve this problem by taking multiple privilege scales into account, but certain models still quantitatively measure based on the sum of privileges across different categories—some are worth more, some less.

Identity politics has a problem with seeing in terms of boxes when we should be thinking in terms of lenses. After all, this is supposedly what intersectionality is all about. Lenses, not boxes.

Academia has the same problem.

The narratology/ludology debate (which seems to be reborn as the formalism discussion) is a perfect example of the problem manifest in games studies. It’s tempting to frame Tetris as a “formalist” game, where Life is Strange might be a more “narratological game.” And indeed, this kind of oversimplification is actually taught in game studies classes for an easy illustration of the historical concept of the debate and an easy way to frame each side’s position.

But what this argument does is put Tetris is a box. Ludology then becomes a box that encapsulates “games like Tetris,” that is to say games that have more focus on mechanics as a pleasure experience than story. Or worse, they become prescriptions for what games are. To me it’s obvious that both sides of the debate yield different results. Neither is what games are or even what any one game is because they are lenses, different ways to see games with potentially different outcomes and implications.

A narratological reading of The Legend of Zelda is going to yield a very different experience of the game than a formalist one. Neither will be wholly “right” or “wrong.” Doing such a reading will not make Zelda a narrative or formalist game anymore than doing a postmodern reading would inherently make it a postmodern game.

Not boxes.

A couple of weeks ago I went to Isis Wenger’s #ILookLikeAnEngineer event. I pictured something like a mini Grace Hopper Celebration. It was a great event: fantastic speakers, impressive attendees, good food, fun photo booths, and professional portraits. Some of those portraits may end up on a billboard in San Francisco. I’m impressed at how well the organizers did with so little time.

A few days ago, the event organizers posted the portraits to Facebook and asked participants to tag themselves. My photo was among them. Here was a moment for me to own the label into which my colleague had generously invited me. Here was a chance for me to share myself in the context of engineering with my friends and family.

Instead of worrying that being an “engineer” it means I can’t also be a designer, I made the decision to own the label. I hit share and announced that I was an engineer.

Because I realized I was being silly. These labels are lenses.

Not boxes.