I mentioned in my previous post that 2020 was a year of self-discovery. Some of the ways I grew this year felt like natural next-step progressions for me. But some were a complete surprise.

I learned last year that I have ADHD. Honestly, before 2020, that never even crossed my mind as a possibility despite me wondering if several close family members might have it. Largely, the fact that I didn’t recognize it in myself was a product of persistent misconceptions of ADHD, especially in how it presents in women. ADHD was for people who couldn’t focus or get things done, people who couldn’t sit still without fidgeting, people who couldn’t follow conversations. And it presents in childhood; surely I would have noticed by now. Besides, I’m successful, and if anything hyper-productive, an over-achiever. I’m organized and communicate well. And I can get absorbed in work for hours or days without batting an eye. I had no idea how normal all of these traits are for people with ADHD, and what a huge barrier to diagnosis they can be.

This has probably been the single most important discovery of my adult life—on a personal level, but especially on a professional and creative level. So I want to share my experience in case any of it helps or resonates. There’s a lot here, so I’ll break it down into sections:

- Some clues I had ADHD that I’d never picked up on

- Reasons I never considered I might have ADHD (misconceptions)

- How I came to realize I had ADHD

- Medication: Fears and Realities

- What this has meant for my creative process

1. Some clues I had ADHD that I’d never picked up on

In reality, most of my symptoms were present in childhood. But also, I didn’t realize they even were symptoms; most were “aspects of my personality” that I had worked very hard to overcome so that I could succeed in school and work. None of them ever registered to me as ADHD. In fact, they just felt “normal” or maybe the product of some kind of perfectionistic anxiety issue. But the signs were definitely there, and many of them I only realized in hindsight. For example:

My work patterns were all-or-nothing.

If I had two weeks to do an assignment, I could not even think about working on it until a real panic set in. Even when I wanted to start working on something before the risk of failure forced me into it, I often felt like I literally couldn’t. But when I did hit a deadline, I could go hard and fast on it for days with no breaks or distractions. But those were my only two modes.

I procrastinated on any task I didn’t really want to do, especially on small, easy tasks if they had negative emotions attached.

This was a habit I spent a long time deconstructing in therapy as a young adult, but it took a lot of work, and the impulse remained even if I could eventually force myself into a task. For example, paying a bill—something which might take 90 seconds with today’s technology—would be something I didn’t really want to do, so I would procrastinate on it until the payment deadline. Calling a doctor or setting up a delivery would only happen when the penalty of not doing it was too great to ignore. I’d always heard people describe ADHD as it being “difficult to do basic tasks,” but for me, the task themselves weren’t difficult. It was actually how easy they were that made it frustrating and confusing. It felt like there was an invisible force field between me and my to-do list. I could really want to do a task, but also be completely unable to muster the motivation to just do it.

When I did get started, it felt like a constant pull away from my task.

I thought this was an anxiety issue, or that I must not want to do the work on an unconscious level, so I was experiencing some manifestation of intense FOMO or perfectionism or imposter syndrome. Usually the pull was toward social media, or news (during COVID lockdown), or videogames—things that felt like they would alleviate that uneasy feeling in the moment. And I should stress here, it was always things that seemed like they would alleviate the anxiety, not things that actually did. Usually the pull away from what I knew I should be doing would make me feel guilty, which would itself cause me anxiety.

I would spend a lot of time on things like list-organizing and “ramping up”.

So while I often couldn’t focus on the tasks I needed to get done, I could spend hours absorbed in productive procrastination, things like cleaning, list-organizing, planning to do the work I couldn’t actually seem to do, or writing articles. I actually suspect this is why I have always had two projects on at once, so that I can bounce back and forth between them and my procrastination is always moving something forward. I certainly found ways to harness my procrastination tendencies, but the fact that they were so strong in the first place when I truly wanted to be working should have been an indicator.

After spending some time on a task, I would feel an intense physical urge to move to a different work space.

Eventually I mapped different work spaces and environments to different tasks so that I could comfortably move around an office throughout the day and could focus my mind on a task based on where I was when performing it, but it was very hard for me to be in one location for more than a couple of hours.

I was constantly anxious about being punctual, prepared, and organized, so I obsessed.

The thought of being late or perceived as underprepared caused me a lot of anxiety. If I realized I was going to be late for something, it was like a panicked scramble set in. Thus I was often over-prepared or arrived an hour early for something so that I wouldn’t risk being a minute late. I’d been late and underprepared a lot as a child, so I way overcompensated for that by obsessing about these things. This was a mental burden I didn’t even realize was weighing on me constantly until it was gone.

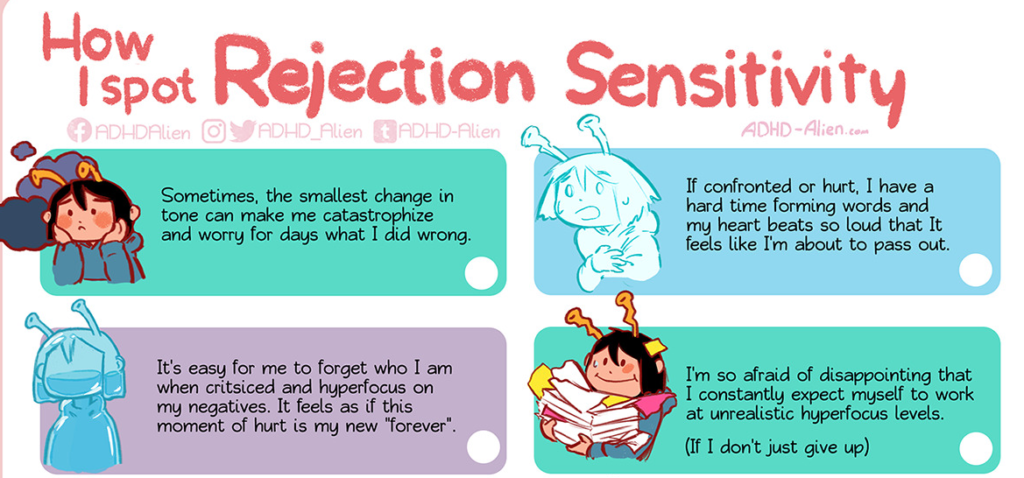

I had classic rejection sensitivity.

I didn’t know what rejection sensitivity dysphoria was, and I thought what I experienced—taking comments from people close to me as expressions of my inadequacy, the fight-or-flight response to an unexpectedly embarrassing situation—was just the anxiety of perfectionism. Rejection sensitive dysphoria is an overwhelming emotional response caused by the feeling that you have disappointed or been criticized by important people in your life. As a young adult, I often took things personally and even ended friendships because I saw things as deep betrayals when they really had nothing to do with me. Rejection sensitivity dysphoria is not actually a diagnostic criteria for ADHD but it is very common in people with ADHD.

I could get absorbed in something for hours, days, or weeks.

This one is one of the most important: I never thought ADHD was even a remote possibility because of the hours I could spend playing games. I did not know hyper-focus was a symptom of ADHD, and if I had, I likely would have suspected it in myself much earlier. I could go into a trance and bang out a paper or art piece by working 3 straight days with no problem. I could play a game for 12 hours without even realizing the time had passed. And I could do this for weeks. Heck, with World of Warcraft circa 2009, I carried that obsession 24/7 for 3 years.

All of my hobbies are dopamine factories.

We don’t know a lot about what causes ADHD, but we do know that it affects your body’s ability to produce and absorb dopamine. It was explained to me thusly: basically people with ADHD are constantly running at a dopamine deficit, so the signal to be motivated to do things doesn’t fire correctly. But your body is still always seeking dopamine, and in fact it’s this seeking that causes people with ADHD to switch from task to task until they find something that does produce it and they latch on. So it’s not surprising that all of the hobbies I’ve stuck with long-term are those that are very high in dopamine production: videogames, running, music/performance, wine-tasting.

I drank a lot of coffee, because it made me feel calm.

People often talked about coffee making them anxious or amped up, which was something I never understood because coffee always made me calm. And in fact, it was one of the few things that would help me when my mind was racing too fast for me to focus on anything (which again, I attributed to being “too anxious to think.”) And this is a common response in people with ADHD: stimulants actually calm them, so many people actually use caffeine to self-medicate before realizing they need stimulants to relax.

I couldn’t sleep because I couldn’t calm my mind before bed.

And before you point to the coffee, the insomnia was often worse with less caffeine. Anyone who knows me with any level of familiarity knows that sleep is something I’ve struggled with my whole life since very early childhood. Even when it’s been “better”, I’ve never had a great relationship with sleep. Insomnia is extremely common in people with ADHD for a myriad of reasons from thoughts racing to hyper-focus on something disrupting sleep schedules to delta-wave disruptions, and I’m sure I’ve hit every single one.

2. Reasons I never considered I might have ADHD (misconceptions)

When we think of ADHD, most of us think about the hyperactive little boy who can’t stay in his seat in classes, the one who “can’t sit still and behave.” Maybe we think about someone who gets distracted a lot or can’t complete tasks—someone who struggles at school or work. Ultimately, these misconceptions get in the way of diagnoses, especially for women.

I’m not hyper.

Hyperactivity is not present in all people with ADHD, despite it being in the name. And hyperactivity is a lot less present in women. There are actually three types of ADHD: inattentive type, hyperactivity type, and a combination of the two. I have the inattentive type, and it is much more common in women.

I don’t act out, I act in.

Almost all of my symptoms had been directed inward over the years: they manifested more as anxieties that I would fail if I didn’t obsess (because I would), than as outbursts or inappropriate movement or missed deadlines. I set up staggering internal rule structures and systems to remember things and keep me organized and they worked. I truly had no idea how much mental toll it was all taking to perform basic tasks because that was normal to me and I wasn’t failing. This is a common experience in women, since girls are told from a very young age to “behave properly” and to lessen their burden and impact on others at the expense of their own comfort and feelings.

I’m successful, productive, and reasonably organized.

In response to struggling with organization through a lot of my childhood, I’d developed very robust systems to help me succeed. Even when there were mental barriers, I could white-knuckle through them to get things done, so they didn’t outwardly manifest as me missing deadlines or being lazy or being late. My obsession with punctuality or how much it stressed me to seem underprepared were things that I channeled inward but they were not very apparent from the outside. But again, I didn’t realize how much I was fighting for things that are basic to other people, and I honestly didn’t even realize how much of a mental burden they were to me until they were gone.

But I can focus on ____ for hours.

Hyper-focus really was the missing piece for me. If I’d known that hyper-focus was a symptom, and that people with ADHD tend to have very all-or-nothing attention drives, I absolutely would have been tested sooner. It is very common for people with ADHD to lose themselves in a hobby or interest, or even cleaning the stove really well once they’ve started, and to be completely absorbed in it for hours.

The biggest barrier for me was actually just recognizing that ADHD was a possibility. Once it actually registered that my normal was not run-of-the-mill procrastination, all of those issues that I’d experienced over my lifetime, all of the flaws I’d tried to overcome, and all of the rules and structure I’d forced on myself starting to feel a lot like symptoms rather than character defects. Everything started clicking into place.

3. How I Came to Realize I Had ADHD

I didn’t realize I had ADHD all at once, the realization came on slowly over a matter of months. I saw ADHD memes that really resonated, but I dismissed them as coincidence. I saw friends being diagnosed who surprised me, but I’m not their doctor.

Then in late 2019, someone close to me revealed that they had been diagnosed as a kid and were going back on medication. Watching their transformation was revelatory. As they adapted to medication, every few days, they would come me with a to new discovery, saying “I would previously experience [this symptom], but now I just feel calm!” and with each new “this symptom” —stress about deadlines, procrastination, obsessions, stress about never finishing things, bursty work cycles, intense fear of vulnerability—I found myself repeatedly thinking, “wow, I feel this symptom too, but I’ve always called it anxiety.”

I had built a lot of coping mechanisms to handle my “anxieties” enough to get things done over the years. I knew I struggled with perfectionism, so I went to therapy and had a LOT of strategies in place to combat that (that’s a whole other post). I knew I struggled with time management and could easily get lost in a single task for too long, so I had an elaborate series of task lists, alarms, checkin calendar events, and rule systems in place to keep me on track and keep me moving from task to task. I knew I did my best work under the pressure of a deadline, so I put micro-deadlines in place throughout my workday to force me into a constant work pace. I knew I physically needed to move locations throughout a day and that I did better when specific tasks were tied to specific locations, work environments, and postures, so I got a co-working membership and moved around the space throughout the day. I was coping with my “anxieties”, but it cost me a lot of overhead and mental bandwidth to constantly check up on myself and to repeat these processes in a loop all day every day.

But when 2020 happened, all of my coping tools were gone. I couldn’t go to my workspace; there was no separation between work and home, so every task felt like I had all the time in the world to do it, which meant I couldn’t get anything done. I couldn’t focus for more than 3-4 minutes without feeling the pull back to the news, COVID numbers, or laundry. I was completely flailing. With my rule systems decimated, all of the “anxiety symptoms” I’d been carefully constructing environmental solutions to avoid were in full, crippling force: my mind was constantly racing too fast for me to grab hold of good ideas; I was distracted and forgetful; I would ignore even the most basic 5-minute tasks because they felt overwhelming. The memes were suddenly a lot more relevant, and I knew something was wrong. But I also thought of how much medication had helped those I knew, so I decided to get tested.

After a couple of questionnaires and an interview about my childhood habits, I was recognized as having it pretty quickly, and was recommended for stimulants.

4. Medication: Fears and Realities

I’m no stranger to medications for mental health, but something about ADHD stimulants felt very different: they’re controlled substances (amphetamines), it’s a whole process to come off them and detox, and they’re literally designed to change how you think—that’s scary! I had a lot of fears before going on stimulants, and this part is especially important for creatives. I want to talk about what I was afraid of and how it has all actually played out for me.

I was afraid of losing the ability to make connections among disparate ideas.

I have always said that my superpower as an academic and as a creative is that “I think in hypertexts.” That is to say, my superpower is finding unlikely connections between disparate ideas. I was really afraid that if I became “more focused” this would somehow “trap my brain into a single lane” and I would lose the ability to find these connections. I was terrified that I would think linearly rather than thinking in links.

I was afraid of giving up the episodes of hyper-focus.

I once heard a bipolar artist explain that she didn’t want to go on medication because she produced so much of her best work during her manias that she worried she would never create great work again. I had a similar worry about writing and my episodes of hyper-focus. Before medication, all of my best work had been produced during episodes of hyper-focus. I worried that if I couldn’t lock in for hours or days, I wouldn’t get nearly as much done or that the work wouldn’t be as cohesive or as inspired.

I was afraid of losing my creativity.

I know the myths about creativity and genius, and yet still I clung to some idea that if my brain were “less random,” I would lose some creative edge. I worried that my mind might become “dulled,” and I just wouldn’t have good ideas anymore. I worried a little that “slowing my brain down” would mean the pool of ideas I had to choose from was smaller.

I was afraid of addiction.

I’ve dealt with a lot of addiction in my family and amphetamines are not a joke. I actually stayed away from things like Adderall in college when others were abusing them for exams, and I was scared of anything I couldn’t just decide to stop taking.

None of these have actually been a problem. If anything, I’m better able to zero in on connections to hard problems. The medication doesn’t take away my ability to hyper-focus, it just allows me to control it. And if anything, I’m more creative.

It turns out, you actually can stop taking it if it’s not right for you; they really start you on a very small dose, and you can generally tell right way if it’s working. For me, it worked wonders.

The realities of going on medication

Going on medication changed my life. I cannot overstate its impacts enough. For as scared as I was to go on medication, its impacts were immediately apparent and it has provided nothing but positive changes for me. All of my obsessions and rules and adaptations and stresses—everything that I previously called anxiety—all just went away. It’s like I was carrying a heavy backpack that I didn’t even realize I was carrying until medication let me take it off.

I never really considered any of my problems to be attention issues per se until I got on medication and realized what my attention could be like—what “normal” people’s attention process is like. I’ll try to describe something that is ultimately indescribable, so please recognize this is as an imperfect attempt to render into words something which can only really be felt but here goes:

My attention had previously been like a laser beam: sharp, singular, and unwavering. Except I didn’t get to point the laser, my emotions did. If something was uncomfortable or boring or just not urgent enough, no matter how hard I tried to point the laser at it, my emotions would yank the laser to something else that seemed more engaging. And sometimes my emotions would just fling the laser beam around, unable to decide where to point it. On medication, my attention is actually a lens with something in the center that captures most of my attention, and things at the periphery that I’m aware of but not distracted by. I can point the lens wherever I want and focus it as sharply or as loosely as I wish. I literally never made the connection on why we call it “focusing” on a task before this. No longer is my attention an all-or-nothing binary, but it is instead a multidimensional gradient. And most importantly, I get to direct it.

Another interesting effect of medication is that I’m also much more in control of emotions. I never felt particularly not in control of my emotions, but I would describe it as feeling like my emotions were a cloud or bubble that surrounded me; I was very much inside my emotions. Now on medication, my emotions feel a little more external to me; they feel like indicators or alarms rather than things I need to work from within. I absolutely still feel them, and they are not less strong per se, but they are less all-encompassing, and they’re much easier to examine, process, take lessons from, and work through. I can also recognize others’ emotions without them filtering through my own emotional haze. This change alone has made me a more effective creator, professional, and leader.

5. What this has meant for my work and creative processes

Medication has absolutely changed my creative process, but those changes are unanimously in ways I consider to be improvements. For everything I was afraid of losing, the reality is that I haven’t lost any of my “superpowers”, I’ve simply gained the ability to control them. This control has manifested in a variety of ways:

I can decide what tasks to focus on and just do them.

And the impacts of that are farther-reaching than they sound. Before medication, my focus was entirely at the whims of my emotions and other factors beyond my control. But I was too achievement-oriented to just ride that out until I felt like working. So instead, I would architect my environments to control my emotions, protect me from triggers, and do everything in my power to stay on task. It was a constant, exhausting battle to complete tasks I didn’t want to do, even when they desperately needed to be done that often left me feeling terrible that I didn’t feel “more motivated” to do very important things. Now the invisible barrier is gone and I can just get things done. I’m constantly locked into a cycle of getting things done, feeling great about getting things done, and moving projects forward in a way that feels rewarding.

I can get into a groove and stay there.

Previously it was very easy to knock me out of a groove, which meant I worked very hard to protect myself from interruptions while working, and any small interruption would make me very grumpy. As you might imagine, this grumpiness becomes harder and harder as you start to lead teams and people need your time and attention to do their work. Now I’m able to work, field a question or request, and jump right back into my own stuff exactly where I left off.

I don’t need to “ramp up” into work, I can just dive in.

Relatedly, it previously took a long time for me to transition into the “right headspace” to do mind-consuming work. Thus, there was usually a long ramp-up process to “get into work mode.” Again, this is not conducive to the natural interruptions that come with leading a team or engaging with collaborators, but it also means that when you have short blocks of time in a day (say, 15 minutes between meetings) it would often feel “not really worth it” to try to “get good work done” since I was likely to spend a lot of that time ramping into work. With that barrier gone, I’m able to utilize those small bits of time, which means my whole work day is actually productive.

My creativity has not diminished.

If anything, the quality of my insights has improved because I can stay with ideas longer, iterate on them, and even walk away to leave them to mature without losing their threads. Being able to return to a thought process I was in the middle of without losing my train of thought means that I can work through the full impact of my ideas more easily, change directions, backtrack, or let things go when they aren’t working. The result is that I pitch better ideas.

I work normal, consistent hours.

This is the one I was actually most afraid of, and it has turned out to be one of the best things to happen to me. Previously, I was at the mercy of when my brain decided something was interesting or urgent enough to hyper-focus on it. This meant that I wasted a lot of time, but then would work for huge stretches of hyper-focus. I was scared that losing the hyper-focus would mean a net loss on productivity, but nothing could be further from the truth. For one, I didn’t actually lose the ability to hyper-focus, only the inability to control it. And more importantly, working at a reasonable, consistent schedule but being able to actually use all of the time in my day productively means that I’m more productive overall and I get more free time! I don’t have to contort my work schedule around when ideas and productivity “happen” to strike.

I can finally just go to sleep.

Again, this one really can’t be overstated. I actually get emotional talking about it because it’s been such a problem for me for so long. Sleep is so important for everything: creativity, productivity, health, everything. And that barrier to falling asleep is finally gone for the first time in my life. I can just go to bed and sleep. Sure, I still worry about things, and sometimes I stay up too late reading in bed or something. But I can sleep if I try, and this change alone makes medication worth it for me.

All of my former rules and structures still help me.

Setting calendar checkins for goals, intentionally building daily habit practices, and learning to adapt my environment to my tasks wasn’t wasted effort for all of those years. If anything, those practices continue to serve me, and I can now relax into my own organizational practices. I know I’m on top of things; I know that my time literally cannot be better-used, so there’s no guilt about having to push deadlines or scope tasks; and I’m able to communicate time estimates and progress to my colleagues from a place of strength and authenticity.